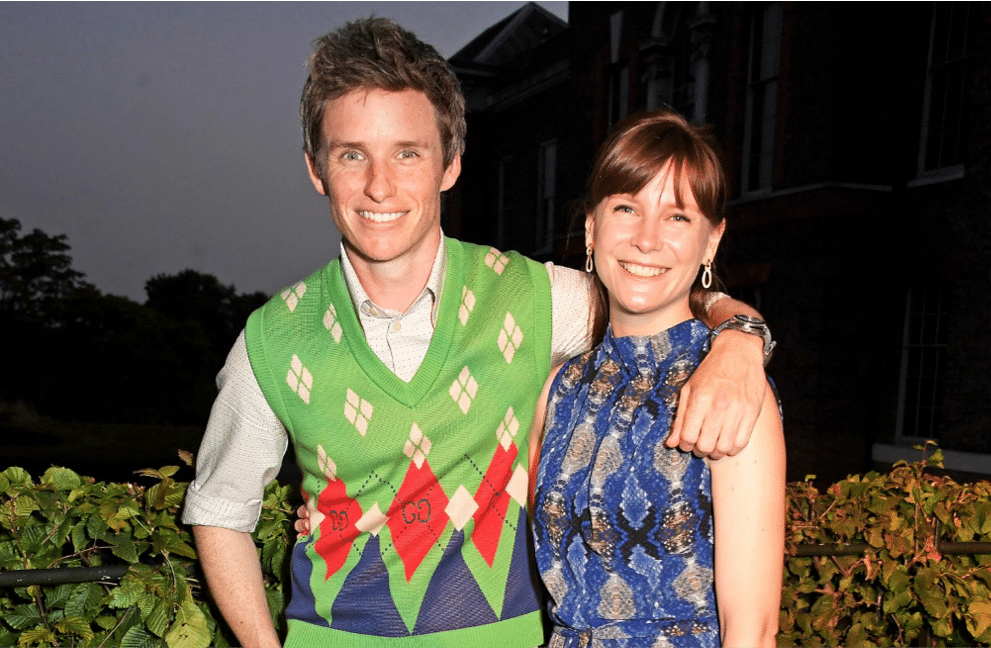

Eddie Redmayne and Rebecca Frecknall DAVE M BENETT/GETTY IMAGES

Director Rebecca Frecknall tells Dominic Maxwell how her dream show came to life when Eddie Redmayne asked to meet her for a drink

The first time she met Eddie Redmayne, Rebecca Frecknall was in tears. It was the start of 2019 and the director was in the West End watching the last performance of her revival of Tennessee Williams’s Summer and Smoke. It had been her big break, had transferred to the West End on a cloud of rave reviews from its run at the Almeida in north London and, more to the point, had been with her in some form for almost ten years since she had first staged it as an end-of-year show for her directing course at the London Academy of Music & Dramatic Art (Lamda). She had no idea, however, that the man sitting in front of her that evening was the Oscar-winning star of The Theory of Everything. They were introduced, they briefly shook hands, “and that was it”, says Frecknall, 35. “I was a bit of an emotional wreck.”

Except that wasn’t it. Something about Frecknall’s spare, evocative, intense production of a hitherto under-loved Williams play — one that came, lest that spareness sound too self-denying, surrounded by an eye-catching semi-circle of seven pianos — had spoken to Redmayne. A month later, while Frecknall was rehearsing a production of Chekhov’s Three Sisters at the Almeida, Redmayne suggested that they meet for a drink. He brought the film and theatre actress Jessie Buckley with him. They were thinking, he told her, of staging Kander and Ebb’s great Weimar Germany-set musical Cabaret. She had never directed a musical, but would she be interested?

Just a bit. “Everyone wants to direct Cabaret,” she says now, “but how often do the rights come up? I don’t think I’ve ever met a director who wouldn’t say they were interested.”

The meeting ended, and Frecknall tried not to think too much about it. That sort of meeting happens when you start getting a bit of success. Actor A meets Director B, they express admiration for one another, Project C might happen six months later . . . or a decade later . . . or never at all. It’s how the business works.

Except that this one, after a year in which Frecknall heard nothing more about it, did. By the end of 2020 she was looking around the Playhouse Theatre in the West End with the producers, with a view to redesigning it radically. In February she was getting the thumbs-up from the sole surviving member of the original creative team, the composer John Kander. (What was his decision-making process? She has no idea.) And since March she has been pretty much full-time on a production of Cabaret that stars Redmayne and Buckley, with co-stars including Omari Douglas (It’s a Sin).

It has taken up so much of her time because Frecknall, as you’ll know if you saw Summer and Smoke or Three Sisters, or her other Almeida productions The Duchess of Malfi and Nine Lessons and Carols, doesn’t do things by halves. What’s more, the idea was already there to turn the Playhouse from a proscenium-arch theatre into an in-the-round cabaret space that would increase the intimacy — and, everyone hopes, the moral reach — of a show that goes from the fun of Weimar-era decadence to the crushing horror of Nazism as the Twenties turn into the Thirties in Berlin.

Is there anything so crass as a “concept” behind her version? Frecknall fights shy of admitting there is since, she points out, the show itself is a concept musical — “the first concept musical”, created in 1966 by the director Hal Prince, the songwriters Kander and Fred Ebb and the book writer Joe Masteroff. The action moves between backstage and onstage, from the depiction of the life of a troubled cabaret performer, Sally Bowles (Buckley), to the straight-to-audience addresses and songs by her and the Kit Kat Club’s emcee (Redmayne, in his first stage role in 11 years). And yet the aim is to ensure that everyone in the audience feels themself truly inside the Kit Kat Club. “What Cabaret as a piece is trying to do is create complicity with the audience,” Frecknall says. “It welcomes the audience in, in order to then do something to them later on. So how do we do that now? How do we pull the rug out from under the audience?”

It is, at least initially, a luxurious and (overused word, but let’s go with it here) immersive experience. A troupe of performers put on routines on all levels of the theatre before the show proper begins, once the audience have made their way through the shimmering gold corridors to the auditorium. Some of that audience will be enjoying pre-show meals and champagne at their tables. Frecknall knows that directing a big show is all about delegation and trusting your team; she hasn’t actually devised the three-course menu herself. However, she and the designer Tom Scutt were involved in choosing the glassware that people drink from, “because it’s part of the world”.

The cost of some of the seats has raised some eyebrows. Look at the official website and there are nights when you can nip in for £30; there are also plenty when the available seats start at £200. Is this show about a doomed elite going to play only to the elite? Frecknall is adamant that it will not. “A quarter of the house is £50 or less, and we’re doing a daily lottery for £25. If you get one of those seats you could end up on a table at the front for that much — a seat that otherwise would cost hundreds.”

Does the pressure ever get to her? Big stars, big prices, big expectations of a known and loved musical? Only the last of those, she insists. The big stars have been a delight to work with. “You come into the rehearsal room and you do not get a sense of some starry hierarchy from Eddie or Jessie — it’s a real company. And the standard I expect from myself is always the same whatever I’m doing, and it’s ridiculously high, and sometimes my anxiety — I suffer from anxiety — can come from the fact that actually I think I often set my bar unachievably high and that’s not helpful.

“So the ticket pricing and all those other elements . . . It’s not helpful for me to think about that. It’s much more about making something that I feel is of the highest standard that it can be.”

Frecknall grew up in rural Cambridgeshire, the middle daughter of two teachers who separated when she was “five or six”. Her father, Paul, who went on to lecture at the University of Bedfordshire, was a big theatre enthusiast — when Frecknall stayed at his place she would often find herself watching his two musical theatre VHSs: Sam Mendes’s production of Stephen Sondheim’s Company and, yes, Cabaret. Her mother, Kate, who retired last year, taught reception; her older sister, Hannah, is a primary school teacher too, and her younger sister, Alice, has just had her first volume of poetry published.

Growing up, Frecknall was as interested in dance as she was in theatre. Then, when she was 15, her father gave her a copy of Peter Shaffer’s play Equus, about a boy who blinds horses. “I remember reading that and kind of going, ‘God. Life will never be the same again.’ It never was, really.”

She went to Goldsmiths College in southeast London to study drama, then to Lamda, where she put on Summer and Smoke in 2010. Two years later she reunited the cast to stage it at the Southwark Playhouse in south London, while she was working as assistant director to Rupert Goold (later to take over the Almeida) on a production of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Goold went to see Summer and Smoke. And when, six years later, she came to work for him as an assistant at the Almeida, he suggested she put it on again.

She didn’t want to repeat herself, but eventually took him up on the offer. The production, she insists, was different from the first one — not least with the arrival of her female lead, Patsy Ferran, and those pianos (there were nine in the original Almeida version).

And all of a sudden, with what was only her second professional production (the first was Julie at Northern Stage in Newcastle in 2016), Frecknall was heading to the West End. It thrilled her, and scared her too. “I suddenly felt exposed in a way I never had been before, and that was a shock to me, how scary that felt. And even that with a show that had actually been successful and had already been reviewed. My work is very personal to me.” She got better at shutting out unnecessary chatter. That meant coming off social media, and staying off social media. “I haven’t looked back.”

Success brings anxieties that you aren’t ready for, she says, especially — understandably — in theatre, where everyone talks a lot about how you’re unlikely to make it, and not so much about what to do once you have made it. “So then I’m a position where I’m trying to accept the fact that things have worked out and not be distrusting of that, and trying to relax and trying to have confidence in the fact that every show I do is not going to be the last show I ever do. Because you live in that world so much when you’re emerging. You just don’t know if you’re ever going to get another opportunity again.

“So life has changed for me in as much as I’m fortunate that I’m able to do what I do. But I still live in a shared house in Charlton [in southeast London]. People can look at directors who are very successful and assume that that aligns with a certain lifestyle, but actually making money in the theatre is really hard.”

And Frecknall isn’t the sort of director who can ricochet from one show to another. She needs to take her time. It’s not just a job to her. The moment the work does become just a job to her, she will give up, she says. Which sounds very idealistic.

“I don’t think it is,” she says. “I think it’s, I’m an artist. And when it becomes a job I’m not an artist any more, and I’ll do something else, I’ll do something less stressful.” Does she have a plan B, then? She laughs. “Not yet . . . but I don’t see that day ever coming.”

There is definitely more work on the horizon. Redmayne and Buckley will be with Cabaret until the beginning of April, at which point Frecknall will cast new leads. After that, there is another Almeida show coming up, a trip to Germany to direct a German-language production of Friedrich Schiller’s play Mary Stuart, and she is working with Florence Welch of Florence and the Machine on a new Broadway musical version of The Great Gatsby.

So while directing hasn’t earned her a mansion flat in Knightsbridge quite yet, it couldn’t be going much better. She might like to run a theatre at one point, she says, but it’s “too soon” now, while she is still setting out her stall.

“Summer and Smoke was a really strong flavour, I didn’t think that people would like it like they did. And I’ve wanted to stay true to myself, and that, and the flavour of work I am excited by. And even doing something like Cabaret, which is a huge title, in the West End with a lot of money and risk behind it, I still recognise it as mine and I think it still has that flavour in it. I’m making the sort of choices I would have been making anywhere else. And what’s amazing is that Eddie and Jessie and the producers have been really behind that.”